#14. SIMILAR SCHEMES ARE THRIVING IN EDINBURGH AND BIRMINGHAM. Edinburgh is unusual in the UK in having a network of off-street, totally traffic-free cycle paths and footpaths throughout the city. Many of these routes, which are used by thousands of cyclists and pedestrians every day, were once railway lines.

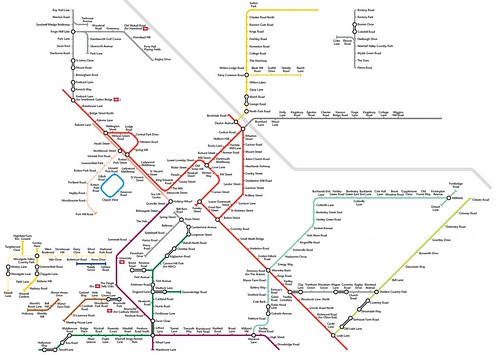

It is apt, then, that a few years ago Mark Sydenham decided to create a simple map of Edinburgh's many off-street pathways, based on the iconic London Tube Map. Designed by Martin Baillie, the map is cleverly called the Edinburgh Innertube map.

Within just a few weeks of its launch, 30,000 copies of the map were distributed throughout Edinburgh. A further 50,000 people have downloaded copies since, or viewed the maps online, and surveys suggest that cycling has gone up by 26% on the paths included on the map. All in all, a big, big success.

So much so that Birmingham has recently followed suit with its own Toptube map, showing the city’s traffic-free cycle network, a scheme which has been similarly successful.

These schemes not only demonstrate how inspiring and useful a Tube-style diagram of cycle routes can be, but also how the efforts of dedicated enthusiasts can make a huge impact. I have great admiration for all the people involved in the Edinburgh and Birmingham projects.

Which invites a question: why are we campaigning for a London Cycle Map, whereas in Edinburgh and Birmingham they’ve just gotten on with it and created their maps?

The reason is that there are some important, and illustrative, differences between the London Cycle Map proposal and those maps.

Based on my understanding derived from conversations with Mark, both the Innertube and Toptube maps show cycle routes which only need to be signed at intersection points, not continuously. They are routes whereby, once you are on the route, you are led along by the natural environment, so that the only time signs are needed when one of these cycle routes intersects with another.

In fact, in most cases signage isn’t necessary at all. By marking stops and intersections on the map with names – such as ‘Middleknowe’ and ‘Lauriston Gardens’ – which correspond to their actual geographical location (e.g. a particular street or landmark), a cyclist can decipher where and when to change routes on the network, or to get on or off it.

This is a very clever way of doing things. It enabled the Edinburgh scheme, for instance, to thrive with minimal initial investment plus a modest (but still impressive) sum of £98,000 in funding which followed. Mark hopes in the future to be able to include various on-street routes on the map, which would require continuous signage. This way, Edinburgh could slowly develop a more comprehensive hybrid cycle network involving both on- and off-street routes.

So would this approach work in London? The answer is yes, but we can – and need to – do things differently here.

If we started out by creating a Tube-style map of off-road routes that don’t need to be signed continuously, not only would we encounter a lack of such routes, we would also find that they aren’t necessarily very useful. Many of London’s off-road routes are more scenic than direct, like a steam railway that doesn’t necessarily take you anywhere you want to go. A map of those routes certainly wouldn’t catalyse a cycling revolution among London’s commuters any day soon.

We would also find that, when we supplemented this skeleton of signage-lite off-street routes, by incorporating streets and on-street signage onto the map and network, the design would rapidly become unacceptably complicated. There just wouldn’t be enough colours to code all the possible routes. We would soon have to start repeating colours, and the whole thing would become very confusing – more like a Jackson Pollock painting than Beck’s inspirational Tube map.

As any manager will tell you, sometimes bottom-up approaches solve problems, and sometimes top-down approaches are needed. Good policy-making consists in recognizing where one or the other is necessary.

Parker’s London Cycle Map is a top-down approach. He has recognised that if we want to create a useful, city-wide network of cycle routes in the sprawling metropolis of London, we need to do so according to a plan. His plan shows how to deploy colours as economically as possible, by using an ingenious system of parallel coloured routes, connecting all areas of the capital. He has eschewed many of London’s off-street cycle routes, which are too minimal to form the basis of an effective network, in favour of the streets of the London Cycle Network. The capital already contains over 2000 kilometres of these safer, quieter streets, which are provisioned with cycle lanes, and Parker’s map includes most of them. If we install road markings and signs on the streets corresponding to Parker’s routes, we could enable Londoners to get from anywhere to anywhere in the capital by following just a few coloured cycle routes, rather than remembering hundreds of turn-rights and turn-lefts.

For reasons of design complexity, and lack of infrastructure, an Innertube or Toptube-style bottom-up approach, using off-street cycle routes, wouldn't be as tailored to the capital as a London Cycle Map is.

That doesn’t mean Mark Sydenham and his colleagues haven’t done a marvelous job in Edinburgh and Birmingham. It means that in London we need to take the baton, but take it to where we need to go. To get there, we need the authorities to put up the signs corresponding to Simon Parker's London Cycle Map.

www.petition.co.uk/london-cycle-map-campaign

Edinburgh's Innertube map

Birmingham's Toptube map