You probably won’t read this as closely as you could do. Try it, and you might find out why it was so hard to.

You probably won’t read this as closely as you could do. Try it, and you might find out why it was so hard to.

The explosive growth of the internet, the inexpensiveness of online publishing, the ease of blogging, tweeting and posting on forums, and environmental fears about depleting the world’s resources: all these factors seem to militate against Cycle Lifestyle’s policy of continuing to print our magazine on paper. Why do we do it?

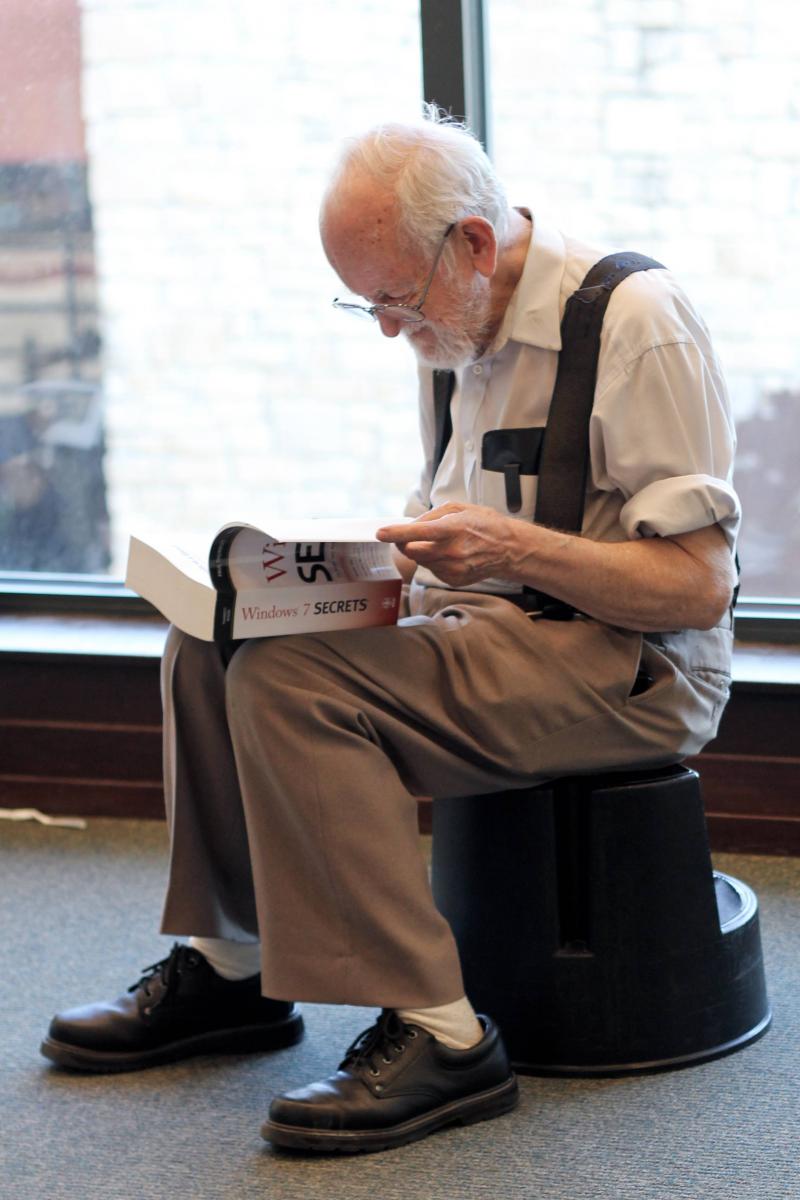

On the positive side, we do it because we want to put a real publication into people’s hands – whether they’re sitting on the tube or bus, relaxing in a student union or cafe, or waiting in the reception area of a school, business or surgery. We want our magazine to be beautiful, colourful and tactile (and smell nice too!), albeit printed sustainably. We want it to be taken home by people and left on the coffee table where it looks inviting, then read again and passed onto friends. Above all, we want our positive message to be as homely-yet-inspiring as cycling itself: something that’s more simple, practical, effective and sociable than the high-tech alternatives.

So why is online content found wanting in these respects? People often talk about ‘webpages’ as if publishing on the internet were just a matter of swapping paper for pixels, a mere change of medium that doesn’t change the message. But it’s hardly that simple. Just as recording a musical performance alters the sound experienced, so the online rendering of written text alters the way it is encountered.

For a start, there are the physical actions and sensory stimuli involved in scrolling and clicking that have no parallels in holding a physical document such as a book or magazine. But much more than this, there are the coloured hyperlinks that saturate webpages, the array of navigational devices in a browser, the online forms to fill out, the numerous different windows or other software applications (such as video games) often in use concurrently, the sporadic alerts from emails, RSS feeders and social networking sites, and the multimedia contents surrounding online text – video, graphic and auditory offerings. Printed pages have no such accompaniments.

So what? In his fascinating book The Shallows (resist the link, I dare you) Nicholas Carr cites dozens of studies by psychologists, neurobiologists and educators which suggest that online content promotes cursory reading and hurried, distracted thinking. The problem is, our concentration gets disrupted by all the usual paraphernalia in our browsers, and so we pay less attention to the words we’re scanning. It takes bigger, bolder, more shocking content – as on the billboards in Piccadilly Circus – to grab our interest when we’re on the internet. CYCLIST KILLS PEDESTRIAN. Are you still concentrating?

It is, of course, possible to think deeply while surfing the net, as it’s possible to casually skim a book or magazine while barely conscious (as anyone who’s been to university will confirm). But the fact is, the web is designed, unlike paper publications, to encourage its users not to get immersed in textual content. The underlying business model of the internet is for its custodians (foremost among them, Google) to profit the more its users hurry through links and pop-ups, like rats running through a maze. Whenever we go online, we willingly enter and bankroll this ‘ecosystem of interruption technologies’, as the writer Cory Doctorow calls it.

And ever-willing we are. The net is utterly compelling to us, even as it bombards us with its distractions. It ‘seizes our attention only to scatter it’, as Carr puts it. ‘We focus intensively on the medium itself, on the flickering screen, but we’re distracted by the medium’s rapid-fire delivery of competing messages and stimuli’. It’s a carnival procession that we can neither take our eyes off, nor get a proper look at.

There’s arguably even something of a narcotic quality to the internet’s hypnotic effects, as is commonly remarked. By yielding up nugget after nugget of new information, the net delivers high-velocity rewards to the nervous system, leading to the repetition of physical and mental behaviors – the same kind of positive reinforcement that’s triggered by any recreational drug.

No wonder research continues to show that reading linear text – the likes of which you get in a plain old book or magazine – leads to better comprehension, remembering and learning than text peppered with links, or surrounded by multimedia content. In paper publications we tend to read sentences as they were written – threaded together in rational connection, forming ever-longer and stronger chains of reasoning – in an alert and calm way that’s quite different to scanning pixilated sentences. In a study of online ‘reading’ conducted by Jacob Nielson, the vast majority of participants were seen to skim words quickly, with their eyes jumping down each page as if tracing out a letter F: a sort of buzzing, intense, hyperactive apathy.

No wonder research continues to show that reading linear text – the likes of which you get in a plain old book or magazine – leads to better comprehension, remembering and learning than text peppered with links, or surrounded by multimedia content. In paper publications we tend to read sentences as they were written – threaded together in rational connection, forming ever-longer and stronger chains of reasoning – in an alert and calm way that’s quite different to scanning pixilated sentences. In a study of online ‘reading’ conducted by Jacob Nielson, the vast majority of participants were seen to skim words quickly, with their eyes jumping down each page as if tracing out a letter F: a sort of buzzing, intense, hyperactive apathy.

If you want to learn anything, that’s F-ing useless. The most significant difference between the two kinds of reading is how they affect our ability to remember what we have been exposed to. The most important factor in forming a memory is attentiveness. The more attention given, the stronger the memory gained. ‘For a memory to persist’, the psychologist Kandel writes, ‘the incoming information must be thoroughly and deeply processed. This is accomplished by attending to the information and associating it meaningfully and systematically with knowledge already established in memory’. Hence, we remember less when we’re inattentively skipping from the top to the bottom of webpages, or surfing between sites – hardly thinking about what we’re doing as we do it – than when we calmly focus on a paper publication resting in our hands (as you would in an old-fashioned library, rather than one of the key-tapping, chat-filled empty spaces they’ve been replaced with).

Key to remembering is the role of ‘working memory’. This is our short-term store of recollections of the past few seconds – what we’re conscious of at any particular time. How effectively we can permanently take new things on board depends on our ability to transfer information from working memory into ‘long-term memory’. Unfortunately, this channel is a bottleneck. Unlike long-term memory, which is vast, working memory is meager. The amount of information it contains at any time is called our ‘cognitive load’, and the heavier the load, the harder it is for us to get to grips with a subject; to assimilate new material; in short, to remember. Studies show that the more complex the material, the more an overloaded working memory impedes the process of remembering it.

The psychologist Sweller cites two main causes of overloading: divided attention and extraneous problem solving. The first is a now-familiar online mischief; the second less so. But problems to solve and decisions to make are plentiful on the internet. How can I make that pop-up go away? Shall I follow the link? Where’s the icon for jumping to the next page? I can’t remember my password, so what’s my mother’s maiden name? As Carr explains: ‘the need to evaluate links and make related choices, while also processing a multiplicity of fleeting sensory stimuli, requires constant mental co-ordination and decision making’.

Research backs this up, showing that online behavior is accompanied by different patterns of brain functioning to reading book-like text. In both cases, there is activity in regions associated with language, memory and visual processing, but internet usage stimulates the prefrontal regions associated with decision-making and problem solving much more. This extra cognitive load makes it harder to sustain concentration and read deeply when staring at a screen.

Books and magazines sometimes have footnotes and other references, of course. But as Carr points out, ‘links don’t just point us to supplemental information – they propel us towards it’. There’s something much more intrusive about being given the choice to open up a whole new vista of information through a mere click of a mouse, than the practically unrealistic choice of journeying back to the library to dig out a dusty volume mentioned in an endnote. The second case is far-removed enough not to count as a distraction or decision. (The same can’t be said in the case of Kindles and other e-readers, which, although decent approximations to paper, are still replete with disruptive features).

Don’t we then miss out on opportunities for enrichment? You might assume so, yet making journals available online and via e-readers seems to have had the opposite effect. Despite the greater ease of cruising amongst volumes, and searching pixilated rather than printed text, the digitization of journals has led to fewer articles being cited by scholars. The problem seems to be that search engines amplify the effects of faddishness; they immediately establish then perpetuate judgments of popularity. Perfect for those who seek the comfort of prevailing opinion.

Another problem with the online reading is that it affects the process of memory consolidation which occurs subsequent to our initial exposure to written content. It takes about an hour for a memory to be fully laid down, and this process, too, is sensitive to distraction. After we’ve read something on the internet, we might kick back with a browse of the latest BBC news, have a laugh at some camels in a car on youtube, or do a quick check of our emails (for the hundredth time that day). All of which is about as helpful to the process of consolidation as a blow to the head. Much better to put down  a book or magazine then enjoy a stroll, jog, or cycle – activities which are especially conducive to the retention of information since they cajole our ancestral brains into readying for a new environment, and therefore new input.

a book or magazine then enjoy a stroll, jog, or cycle – activities which are especially conducive to the retention of information since they cajole our ancestral brains into readying for a new environment, and therefore new input.

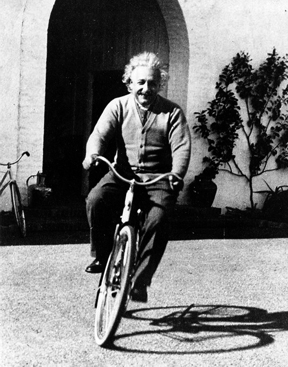

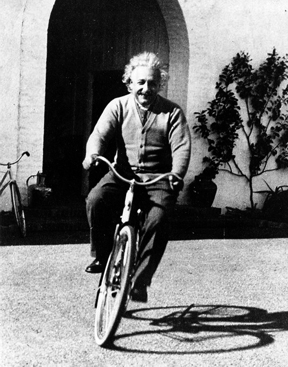

‘The net’s cacophony of stimuli short-circuits both conscious and unconscious thought, preventing our minds from thinking either deeply or creatively’, Carr surmises. That means both fewer recollections and fewer Eureka moments. It is said that Einstein came up with his theory of relativity on a bicycle, and that Newton conceived of gravity while reposing under a tree. It’s hard to imagine they’d have done the same while playing minesweeper, or refreshing the football scores.

The internet turns us into mere ‘decoders of information’, warns linguist Maryanne Wolfe, because it inspires fewer of the rich mental connections that printed words do. Other commentators shrug their shoulders, opining that hyperspace’s sprawling interconnections are more comprehensive than our intellects could ever be, and that personal imagining will even be enhanced – liberated – now we’ve outsourced our knowing and synthesizing to a greater power. People often mention the example of calculators in schools when arguing that the internet is a useful cognitive resource. When schoolchildren first began outsourcing their arithmetic skills to machines there were warnings in some quarters that reduced mathematical competence would follow. The concerns turned out to be misguided: calculators relieved pressure on kids’ working memories, thus creating the cognitive space for a deeper understanding of abstract mathematical principles.

Might the internet similarly create space for richer thought? No, for the simple reason that going online puts more pressure on our working memories, not less – so we remember less as a result. ‘When we start using the web as a substitute for personal memory, bypassing the inner processes of consolidation, we risk emptying our minds of their riches’, warns Carr.

When you think about it, the idea that you could get cleverer and more imaginative by outsourcing your memory to a machine is silly. What else are you going to think about if not all the wonderful things you’ve personally learned? ‘We don’t constrain our powers when we store new long-term memories, we strengthen them’, observes Carr. ‘With each expansion of our memory comes an enlargement of our intelligence’. ‘Thoughts without content are empty’, the philosopher Kant remarked more than two centuries ago.

So if the internet isn’t such a boon to us as individual thinkers, what about its potential for bringing people together? Open-source technology has its upsides, for sure – Wikipedia being the foremost example – yet even the net’s much-touted ability to ‘connect people’ has a darker side. When we post facebook or twitter updates, poke our ‘friends’, blog our latest musings, rant on forums, or send instant messages between bursts of more constructive online activity, our social standing plays on our minds. We’re wondering: will we get the replies and positive social feedback we crave? We feel a little more self-conscious than usual, anxious even.

No doubt, this intensifies our involvement with the medium, but we’re also more distracted, and so we absorb its written messages less effectively: we take out less than we put in. (Skyping can be just as bad. I suggest switching off the screen with your own face on it, otherwise you’ll become preoccupied with gazing at yourself from that interesting slightly-off-centre camera angle, rather than the person you’re supposed to be ‘face to face’ with.)

Evolutionary psychologists emphasise the importance of socializing for human beings in general. We are highly attuned to information about group relations, because we descend from ancestors who lived in a hostile environment as close-knit bands of hunter-gatherers, dependent on co-operative communication for survival, and on gossip or slander for the more competitive business of reproducing. No wonder then that so many of us today are networking and socializing so avidly online: our evolved brains are telling us to take it all in or get left behind in the quest for mutual understanding.

If that sounds like an urbane, logical progression, then the science of nutrition offers a cautionary tale. Millions of years ago, sugars and fats were valuable but scarce sources of energy, so our ancestors evolved an instinct for gorging themselves on certain foods whenever the opportunity arose. Today, as their descendents, we feel compelled to feast on sweets and Big Macs; yet with scarcity no longer an issue, we’re getting fatter and fatter. Perhaps our appetite for social communication is similarly being chronically over-stimulated in the modern world – with the internet burdening us with excessive amounts of social information, clogging our minds like cholesterol.

Most worrying of all, there may be a narcotic character to our online communications, too. When using social networking sites we feel good momentarily, but we fail to derive the real benefits of real interaction – the practical help, moral support, guidance, wisdom, intimacy and shared activities which come from belonging to a real community. (Think Swiss Family Robinson rather than Myspace). Just as a recreational drug gives its users a mirage of happiness that’s unaccompanied by any tangible resources for thriving in the world, social networking gives us a fleeting sense of belonging that’s devoid of the physical experiences of companionship and friendship that usually accompany such an emotion. Phony happiness can be mainlined or online.

If that sounds melodramatic, consider the facts. In Britain, our levels of civic, religious, political, charitable and informal social participation – what sociologists refer to as ‘social capital’ – have been plummeting since the middle of the twentieth century. These are the kinds of homely, practical and caring interactions that make us happy individually and collectively, and make us feel both more free and secure. And we’re losing interest in them, more so than ever.

Perhaps the reason for our indifference is that we’re changing as people as a result of our technological reliance and (most recently) internet usage. At the touch of a button, we can now access a torrent of online information; precisely the kind of intensive, interactive, repetitive and addictive undertaking that has been shown to yield strong, rapid alterations in neural circuitry. As a society, we may be in danger of ending up like sad addicts who clamour fo r the next hit (and do whatever it takes financially to get it) but who’ve forgotten how to be really, truly happy. It isn’t called a ‘Crackberry’ for nothing.

r the next hit (and do whatever it takes financially to get it) but who’ve forgotten how to be really, truly happy. It isn’t called a ‘Crackberry’ for nothing.

Collectively and individually, the internet takes its toll. It ‘turns us into lab rats constantly pressing levers to get tiny pellets of social or intellectual nourishment’, laments Carr. He continues:

"The great danger we face as we become more intimately involved with our computers – as we come to experience more of our lives through the disembodied symbols flickering across our screens – is that we’ll begin to lose our humanness, to sacrifice the very qualities that separate us from machines. The only way to avoid that fate is to have the self-awareness and the courage to refuse to delegate to computers the most human of our mental activities and intellectual pursuits."

Think about it: are you really happy for your personality and friendships to be wired by the same geeks that wire your computer? Because that’s the risk, suggests Carr:

"When we go online, we’re following scripts… algorithmic instructions that few of us would be able to understand even if the hidden codes were revealed to us. When we search for information through Google or other search engines, we’re following a script. When we look at a product recommended to us by Amazon, we’re following a script. When we choose from a list of categories to describe ourselves or our relationship on facebook, we’re following a script… I continue to hold out hope that we won’t go gently into the future our computer engineers and software programmers are scripting for us."

As the editor of Cycle Lifestyle I too believe that standing up to the scripters is the right thing to do. I believe there are not just business reasons, but ethical reasons for printing our magazine (just as there are ethical as well as business reasons for promoting cycling in the first place). One of my heroes, Steven Pinker, is more nonchalant, advising that if people don’t want to be distracted by technology they should simply switch it off. But the (ethical) point is precisely that not everybody has the self-awareness of a professor of psychology; so lots of people don’t realize the harm their internet usage may be doing them. I’m criticizing the internet for the same reason I criticize alcohol or tobacco companies who make their products seem attractive to teenagers. (And, having worked in a secondary school, I’ve seen firsthand the scrambling, antagonizing effects of computers on young minds.)

But doesn’t that make me a hypocrite? I run a website – and make money from it – and I’m publishing these very words online! Shouldn’t I practice what I preach and print them instead? In the eighties there was a TV programme called Why Don’t You? which advised viewers to ‘switch off the television and do something more interesting instead’. As a kid I found this idea intriguing, and today I can’t imagine producers getting away with a reflexive critique like this – biting the hand that feeds them. But I’ve never thought the programme was hypocritical. If people are shouting too loud, you’ve got to hush them more loudly to silence them; and if people are standing up in a football crowd, you’ve got to stand over them to usher them back into their seats. Sometimes you have to join them in order to beat them, and so using a medium to criticize that medium is a perfectly legitimate approach. Sometimes the hand that feeds you is also holding you captive.

You probably won’t read this as closely as you could do. Try it, and you might find out why it was so hard to.

You probably won’t read this as closely as you could do. Try it, and you might find out why it was so hard to. No wonder research continues to show that reading linear text – the likes of which you get in a plain old book or magazine – leads to better comprehension, remembering and learning than text peppered with links, or surrounded by multimedia content. In paper publications we tend to read sentences as they were written – threaded together in rational connection, forming ever-longer and stronger chains of reasoning – in an alert and calm way that’s quite different to scanning pixilated sentences. In a study of online ‘reading’ conducted by Jacob Nielson, the vast majority of participants were seen to skim words quickly, with their eyes jumping down each page as if tracing out a letter F: a sort of buzzing, intense, hyperactive apathy.

No wonder research continues to show that reading linear text – the likes of which you get in a plain old book or magazine – leads to better comprehension, remembering and learning than text peppered with links, or surrounded by multimedia content. In paper publications we tend to read sentences as they were written – threaded together in rational connection, forming ever-longer and stronger chains of reasoning – in an alert and calm way that’s quite different to scanning pixilated sentences. In a study of online ‘reading’ conducted by Jacob Nielson, the vast majority of participants were seen to skim words quickly, with their eyes jumping down each page as if tracing out a letter F: a sort of buzzing, intense, hyperactive apathy. a book or magazine then enjoy a stroll, jog, or cycle – activities which are especially conducive to the retention of information since they cajole our ancestral brains into readying for a new environment, and therefore new input.

a book or magazine then enjoy a stroll, jog, or cycle – activities which are especially conducive to the retention of information since they cajole our ancestral brains into readying for a new environment, and therefore new input. r the next hit (and do whatever it takes financially to get it) but who’ve forgotten how to be really, truly happy. It isn’t called a ‘Crackberry’ for nothing.

r the next hit (and do whatever it takes financially to get it) but who’ve forgotten how to be really, truly happy. It isn’t called a ‘Crackberry’ for nothing.